NHD Paediatric Hub

Faltering growth: an update

Kate heads up our Paediatric Hub this month. Here she focuses on faltering growth and the promotion of healthy nutritional support.

Twitter : @kate_roberts

Kate Roberts, RD

Senior Specialist Dietitian

Faltering growth refers to a notable disruption in the anticipated growth rate when compared with other children of similar age and gender during early childhood. This term is descriptive, and it is crucial to investigate the underlying causes.

Typically, faltering growth is observed in young children, particularly babies, rather than older children or teenagers. Although a weight loss of up to 10% of birth weight is common in the initial days of life, it is usually regained by the age of three weeks once feeding is established.

Faltering growth, occurring beyond the early days of life, is characterised by a slower-than-expected rate of weight gain. (1)

Weight faltering is defined as: weight declining through centile spaces, having low weight for height, or experiencing no catch-up from a low birth weight. Growth faltering, on the other hand, involves crossing down through length/height centile(s) in addition to weight, with a focus on having a low height centile or height below what is expected based on parental heights.

In the UK, growth in children is monitored using growth charts that combine World Health Organisation (WHO) standards and UK birth/preterm growth data.(2) These charts include centiles, marking the weight or height below which a specific percentage of children matched by age and gender will fall. For example, the 25th percentile indicates that 25% of children are below that point.

A child's growth parameters are plotted on these charts to visually track growth over time. If a child gains weight more slowly than expected, measurements will move to a lower centile. Healthy children typically progress consistently along a growth centile. The UK WHO growth charts are available from the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) website, with separate charts for boys and girls, very preterm infants, children with health issues, and those with Down's syndrome.

The British Medical Journal (BMJ) in 2023 produced a Best Practice guide for Faltering Growth, which can be found here...

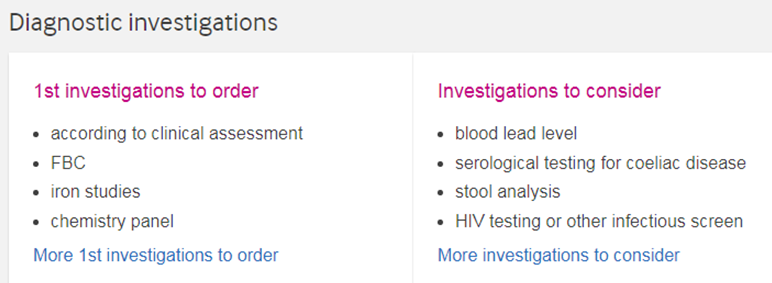

The following tables summarise key diagnostic factors, risk factors and investigations:(3)

Understanding growth patterns

Patterns can include weight declining through centile spaces, having low weight for height, or experiencing no catch-up from a low birth weight. The following patterns enable healthcare professionals to identify faltering growth in children and address potential issues:

Poor parallel lines:

Observing poor parallel lines on growth charts may indicate a deviation from the expected growth trajectory. This visual cue prompts healthcare professionals to investigate potential underlying causes.

Discrepancies in family pattern:

Comparing a child's growth pattern with that of their family can reveal noteworthy differences, providing valuable insights into potential genetic or environmental influences on growth.

Retrospective rise:

A retrospective rise in growth charts, indicating a previous period of faltering growth, is another noteworthy pattern. Recognising this trend enables healthcare professionals to address historical factors contributing to sub-optimal growth.

Saw-tooth pattern:

The presence of a saw-tooth pattern, characterised by irregular ups and downs in growth, may indicate intermittent challenges affecting a child's development.

Dispelling socioeconomic stereotypes:

Contrary to traditional beliefs associating faltering growth with low socioeconomic status, recent research has debunked this notion. Studies have shown that the link between FG and socioeconomic status is not as straightforward as previously assumed. While there may be a larger association between neglected children and faltering growth, this correlation does not equate faltering growth with neglect.(4,5)

Nutritional support

Nutritional support for faltering growth involves early intervention, starting with lactation support for breastfeeding infants and additional formula supplementation when necessary.(6) In older infants and children, nutritional supplements and fortified foods can address nutrient deficiencies.

The goal is sustained weight gain without prescribed supplements, and regular assessments are crucial. Factors considered include weight change, linear growth, intake of other foods, tolerance, adherence and parental views.(7,8)

Responsive feeding

An evaluation of 286 children aged 6-36 months revealed significant but modest weight recovery, emphasising the importance of factors like access to healthy food, promoting child autonomy, and responsive feeding. Responsive feeding recognises the bidirectional nature of feeding, emphasising the child's cues and promoting autonomy.(9)

Nutritional supplements should only be used in combination with encouraging children to eat family foods as appropriate. Early childhood is crucial for developing healthy eating habits. Multi-disciplinary support can reduce malnutrition severity & feeding difficulties.(10)

Promoting access to nutritious food

Promoting access to nutritious food involves advising families to incorporate a varied and healthy diet, along with boosting calorie intake through the addition of butter, oil, cheese, or peanut butter. It is emphasised that any nutritional supplements should be administered after meals, rather than serving as replacements for meals.

Encouraging healthy eating habits involves establishing consistent routines for family meals and snacks, discouraging grazing, minimising distractions, and fostering enjoyable conversations during meals.

Promoting appetite and autonomy in children entails actively involving them in meal preparation, when feasible, and encouraging them to interact with food by touching and picking it up to enhance their appetite.

Videoing the child and caregiver during meals can be a useful tool for education on modelling positive behaviours and responding to their child's cues during the feeding process.

CONCLUSION

It's crucial to emphasise that faltering growth is not a disease but rather a diagnosis of sub-optimal growth. By recognising it as such, healthcare professionals can approach the issue with a holistic perspective, understanding that various factors contribute to a child's growth trajectory. As our understanding of faltering growth evolves, it becomes evident that the roots of this phenomenon are more intricate than previously thought. Healthcare professionals must be attuned to diverse growth patterns and discard simplistic associations with socioeconomic status. This shift in perception allows for more targeted and effective interventions, focusing on the underlying causes of faltering growth rather than stigmatising it as a standalone health issue.

References

- https://patient.info/doctor/faltering-growth-in-children; https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng75

- https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/growth-charts

- https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/747?q=Faltering%20growth&c=suggested

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2065961

- https://www.bmj.com/content/345/bmj.e5931.long

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34725219/\0

- https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/747/pdf/747/Faltering%20growth.pdf

- https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng75

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pmc/articles/PMC4769915

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34725219/